Food Safety With Acidity

This post is a deep-dive on how to prevent food spoilage and foodborne illness using acidity.

It’s part of my broader framework on food safety, which aims to be clearer and more actionable for home cooks than existing food safety guidelines.

WHAT’S THE POINT?

Harmful bacteria, parasites, mold, and viruses might be in your food. To reduce the chances of food spoilage and foodborne illness caused by these pathogens, you need to both:

Kill any existing pathogens in your food. These pose the most immediate risks. You should kill them (or reduce them to safe levels) where possible.

Prevent any new pathogens from growing in your food. If you haven’t totally killed the existing pathogens in your food (or if your food is exposed to other pathogens after the fact), the few that remain will multiply over time. This is especially important for foods that you aren’t eating right away (e.g. food you are storing or cooking over multiple hours)

Acidity can’t kill existing pathogens in your food, but it can prevent new pathogens from growing. In that sense, acidity is the ultimate preservative. This guide will start with a few simple rules then dive into details (so you know when it is safe to break the rules!).

THE CHEAT SHEET

To kill existing pathogens

Acidity is not an effective means for killing harmful microorganisms or viruses. To kill existing pathogens in your food, you pretty much need to use temperature. To learn how, check out my deep-dive on temperature control here.

To prevent new pathogens from growing

Any food substance that measures 4.6 or lower on the pH scale is generally considered acidic enough to prevent growth of harmful microorganisms and can be kept at room temperature. Common foods with pH lower than 4.6 include:

Vinegars (2.5 pH) and foods stored submerged in vinegar

Lacto-ferments (3.6 pH), including lacto-fermented hot sauces

Lemon juice (2.3 pH)

If you make a sauce or lacto-ferment that doesn’t measure to 4.6 pH, you can simply add more vinegar or acid powder until the pH measures low enough.

THE DEtails

About acidity

For our purposes, acidic is synonymous with sour. And this sourness can be measured on a scale: the pH scale. pH means “potential of hydrogen”.

The pH scale is from 1 to 14. Low numbers (pH of 1-6) are acidic, high numbers (pH of 8-14) are alkaline, and 7 is neutral. The pH scale is logarithmic, which means that solutions with a pH of 3 are actually 10 times more acidic than solutions with a pH of 4. The pH of various foods are readily available online. For example:

Milk: 6.65 pH

Carrots: 6.14 pH

Beef: 5.5 pH

Apples: 3.6 pH

Ketchup: 3.9 pH

Elsewhere (particularly with vinegars), acidity is measured as a percentage. Most vinegars are 5% acidity. This percentage refers to the percentage of the solution that is acetic acid (the type of acid in vinegar). Unfortunately, you can’t do a direct conversion from acid percentage to pH because the other components of a particular vinegar (i.e. the other 95%) can increase or decease the pH.

Want to learn more about cooking with acidity? See my post on the types of acidity.

To Kill Existing Pathogens

Acidity doesn’t kill existing most harmful existing bacteria. Instead, acidity merely slows their flow; as soon as harmful microorganisms in acid are returned to neutral water, they regain mobility.

This is why it’s a common misconception that ceviche is “cooked” by citrus juice. The proteins in the fish are denatured as if they were cooked, but existing bacteria don’t die. For this reason, regardless of whether you use acid or not, you should always use fish that is fresh (or was frozen fresh) and avoid the temperature danger zone when eating raw fish.

TO PREVENT NEW PATHOGENS FROM GROWING

Acidity is an effective and foolproof means to prevent new pathogens from growing. That’s why acidity (especially in the form of vinegar brines and lacto-ferments) has been used for many hundreds of years to preserve food and minimize waste.

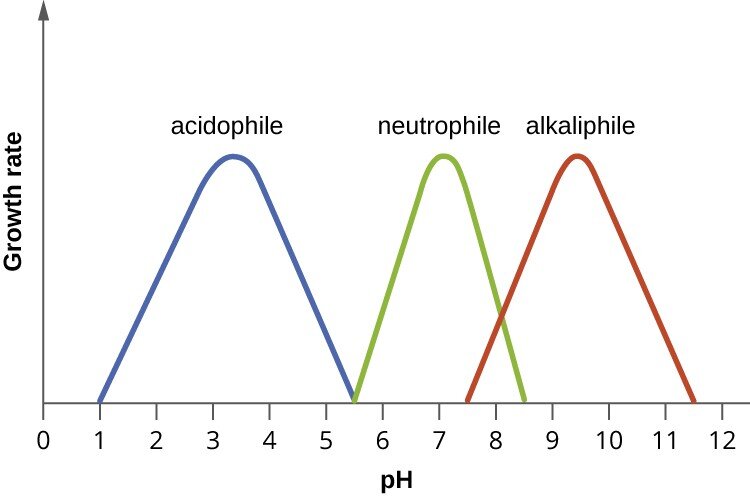

Any food substance that measures 4.6 or lower on the pH scale is generally considered acidic enough to prevent growth of harmful microorganisms and can be kept at room temperature. This means that you can ignore the temperature danger zone for your vinegars (2.5 pH) and lacto-ferments (3.6 pH) with adequate acidity. While acidophile bacteria (like lactobacillus) grow at this temperature, they are generally safe.

If you’re making a dressing, hot sauce, or lacto-ferment, it’s worthwhile to measure the pH before you deem the food shelf-stable. Thankfully, measuring pH is easy, and pH strips are super cheap (though the resolution is low). For more accurate readings up to 0.01, consider buying a pH meter.

If you make a sauce that doesn’t measure to 4.6 pH, you can simply add more vinegar or acid powder until the pH measures low enough.

On vinegar brines

Vinegar brines (e.g. vinegar pickles) usually don’t use pure vinegar. More typically, they are a mix of 50% water and 50% vinegar with 5% acidity. Even at 50% dilution, vinegars with 5% acidity typically produce foods that are well below the 4.6 pH threshold.

You might be tempted then to further dilute your vinegar brine until it reaches a pH closer to 4.6. This is possible, but keep in mind that the acidity of your brine when you assemble the ingredients will not be the same as the acidity of your brine after the ingredients have sat in the brine for a significant period of time. That’s because over many weeks, your brine (which is high in acid) and your food (which is lower in acid) will gradually find acid equilibrium. The higher pH in the food, the more the pH of your brine will increase. So be sure to test the acidity after a few days to ensure it is still below 4.6.

WAYS TO BREAK THE RULES

Don’t want a food with 4.6 pH or lower? There are other ways to prevent new bacteria from forming.

Avoid the temperature danger zone. You don’t need to worry about acidity if you are following the temperature food safety guide.

Decrease the water activity level to 0.85 or lower. Low water activity foods are protected from new bacteria growth.

Use a combination of water activity and acidity. Foods with pH of 5.0 are shelf stable when water activity is 0.9 or lower. See table 4 in this document for more interaction effects.

FAQs

Does lime cook fish or kill bacteria? No. Harmful bacteria, mold, and viruses are not killed by lime, lemon, or other acids. If you are planning on eating raw fish, you should:

Choose a fish with no or low risk of parasites. These are either shellfish, types of tuna, or fish that have been frozen specifically for this purpose. I am personally willing to take the parasite risk with mackerel, sea bass, farmed rainbow trout, halibut, turbot, and snapper. I do not buy freshwater fish as the chances of parasites are high. I also do a visual inspection for parasites (they look like little worms).

Eliminate the chance of bacterial infection. This requires buying fish that is fresh (or that was frozen fresh), keeping the fish out of the temperature danger zone, and keeping your work station clean. I buy whole fish (rather than filets, except with tuna) and I eat my fish the day I buy it.